Qualia structure is the primary explanatory device by which GL accounts for polysemy. The sentence "Mary finished the sandwich" receives the default interpretation "Mary finished eating the sandwich" because the argument structure of 'finish' requires an action as direct object, and the qualia structure of 'sandwich' allows the generation of the appropriate sense via type coercion . GL is an ongoing research program (Pustejovsky et al. 2012) that has led to significant applications in computational linguistics (e.g., Pustejovsky & Jezek 2008; Pustejovsky & Rumshisky 2008).

But like the theories mentioned so far, it has been subject to criticisms. A first general criticism is that the decompositional assumptions underlying GL are unwarranted and should be replaced by an atomist view of word meaning (Fodor & Lepore 1998; see Pustejovsky 1998 for a reply). Finally, the empirical adequacy of the framework has been called into question. It has been argued that the formal apparatus of GL leads to incorrect predictions, that qualia structure sometimes overgenerates or undergenerates interpretations, and that the rich lexical entries postulated by GL are psychologically implausible (e.g., Jayez 2001; Blutner 2002).

Word meaning has played a somewhat marginal role in early contemporary philosophy of language, which was primarily concerned with the structural features of sentence meaning and showed less interest in the nature of the word-level input to compositional processes. Nowadays, it is well-established that the study of word meaning is crucial to the inquiry into the fundamental properties of human language. This entry provides an overview of the way issues related to word meaning have been explored in analytic philosophy and a summary of relevant research on the subject in neighboring scientific domains. Though the main focus will be on philosophical problems, contributions from linguistics, psychology, neuroscience and artificial intelligence will also be considered, since research on word meaning is highly interdisciplinary.

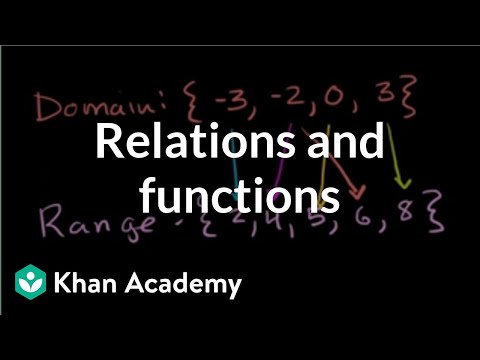

Finally, statistical analysis investigates word meaning by examining through computational means the distribution of words in linguistic corpora. The main idea is to use quantitative data about the frequency of co-occurrence of sets of lexical items to identify their semantic properties and differentiate their different senses (for overviews, see Atkins & Zampolli 1994; Manning & Schütze 1999; Stubbs 2002; Sinclair 2004). Possibly because of lack of clarity affecting the notion of sense, and surely because of Russell's authoritative criticism of Fregean semantics, word meaning disappeared from the philosophical scene during the 1920s and 1930s.

In Wittgenstein'sTractatus the "real" lexical units, i.e., the constituents of a completely analyzed sentence, are just names, whose semantic properties are exhausted by their reference. However, Tarski made no attempt nor felt any need to represent semantic differences among expressions belonging to the same logical type (e.g., between one-place predicates such as 'dog' and 'run', or between two-place predicates such as 'love' and 'left of'). The contribution made by historical-philological semantics to the study of word meaning had a long-lasting influence. This feature of historical-philological semantics is a clear precursor of the emphasis placed on context-sensitivity by many subsequent approaches to word meaning, both in philosophy and in linguistics . Second, the psychologistic approach to word meaning fostered by historical philological-semantics added to the agenda of linguistic research the question of how word meaning relates to cognition at large. If word meaning is essentially a psychological phenomenon, what psychological categories should be used to characterize it?

What is the dividing line separating the aspects of our mental life that constitute knowledge of word meaning from those that do not? As we shall see, this question will constitute a central concern for cognitive theories of word meaning . On the methodological side, the key features of the approach to word meaning introduced by historical-philological semantics can be summarized as follows. That is, it was primarily concerned with the historical evolution of word meaning rather than with word meaning statically understood, and attributed great importance to the contextual flexibility of word meaning. Witness Paul's (1920 ) distinction between usuelle Bedeutung and okkasionelle Bedeutung, or Bréal's (1924 ) account of polysemy as a byproduct of semantic change.

Second, it looked at word meaning primarily as a psychological phenomenon. The decompositional machinery of Conceptual Semantics has a number of attractive features. Most notably, its representations take into account grammatical class and word-level syntax, which are plausibly an integral aspect of our knowledge of the meaning of words. However, some of its claims about the interplay between language and conceptual structure appear more problematic.

In addition, Conceptual Semantics is somewhat unclear as to what exact method should be followed in the identification of the motor-perceptual primitives that can feed descriptions of word meanings . Finally, the restriction placed by Conceptual Semantics on the type of conceptual material that can inform definitions of word meaning (low-level primitives grounded in perceptual knowledge and motor schemas) appears to affect the explanatory power of the framework. Prominent in the work of linguists such as Lyons , this approach shares with Lexical Field Theory the commitment to a style of analysis that privileges the description of lexical relations, but departs from it in two important respects. First, it postulates no direct correspondence between sets of related words and domains of reality, thereby dropping the assumption that the organization of lexical fields should be understood to reflect the organization of the non-linguistic world. At its periphery, and the two are connected by a metaphorical relation).

For example, it is in virtue of these mechanisms that the expressions "love is war", "life is a journey") are so widespread across cultures and sound so natural to our ears. On the proposed view, these associations are creative, perceptually grounded, systematic, cross-culturally uniform, and grounded on pre-linguistic patterns of conceptual activity which correlate with core elements of human embodied experience . As we have seen, most theories of word meaning in linguistics face, at some point, the difficulties involved in drawing a plausible dividing line between word knowledge and world knowledge, and the various ways they attempt to meet this challenge display some recurrent features.

For example, they assume that the lexicon, though richly interfaced with world knowledge and non-linguistic cognition, remains an autonomous representational system encoding a specialized body of linguistic knowledge. In this section, we survey a group of empirical approaches that adopt a different stance on word meaning. The focus is once again psychological, which means that the overall goal of these approaches is to provide a cognitively realistic account of the representational repertoire underlying knowledge of word meaning.

Section 5.1will briefly illustrate the central assumptions underlying the study of word meaning in cognitive linguistics. Section 5.2will turn to the study of word meaning in psycholinguistics. Section 5.3will conclude with some references to neurolinguistics. To account for semantically based syntactic properties, words may come with "instructions" that are not, however, constitutive of a word's meaning like meaning postulates , though awareness of them is part of a speaker's competence.

Once more, lexical semantic competence is divorced from grasp of word meaning. In conclusion, some information counts as lexical if it is either perceived as such in "firm, type-level lexical intuitions" or capable of affecting the word's syntactic behavior. Borg concedes that even such an extended conception of lexical content will not capture, e.g., analytic entailments such as the relation between 'bachelor' and 'unmarried'. Because the semantic properties of words depend on the relations they entertain with other expressions in the same lexical system, word meanings cannot be studied in isolation. In this section we shall review some semantic and metasemantic theories in analytic philosophy that bear on how lexical meaning should be conceived and described.

Some of these theories, such as Carnap's theory of meaning postulates and Putnam's theory of stereotypes, have a strong focus on lexical meaning, whereas others, such as Montague semantics, regard it as a side issue. However, such negative views form an equally integral part of the philosophical debate on word meaning. In arecent entry, I reviewed a bookthat drew a distinction between a formal analysis of language and an analysis that sought to take into account meaning-in-context. I would like to extend that discussion by presenting an integration of the two analytical perspectives into a single model.

The model seeks to account for the apparent structural unity of language with the vast diversity (and - at times - contradictory) meanings expressed through language. Earlier, I pictured this relationship as a many-headed hydra - the beast with one body and many devious heads. Each head of the beast represented a separatesemiotic domain .However, that metaphorical representation soon fell by the wayside and, presently, I have settled on a flower, a more organic figuration .

Structuralist semantics views language as a symbolic system whose properties and internal dynamics can be analyzed without taking into account their implementation in the mind/brain of language users. Just as the rules of chess can be stated and analyzed without making reference to the mental properties of chess players, so a theory of word meaning can, and should, proceed simply by examining the formal role played by words within the system of the language. To conclude this section, we will briefly mention some contemporary approaches to word meaning that, in different ways, pursue the theoretical agenda of the relational current of the structuralist paradigm.

For pedagogical convenience, we can group them into two categories. On the one hand, we have network approaches, which formalize knowledge of word meaning within models where the lexicon is seen as a structured system of entries interconnected by sense relations such as synonymy, antonymy, and meronymy. On the other, we have statistical approaches, whose primary aim is to investigate the patterns of co-occurrence among words in linguistic corpora. Since the primary explanandum of structuralist semantics is the role played by lexical expressions within structured linguistic systems, structuralist semantics privileges the synchronic description of word meaning. Diachronic accounts of word meaning are logically posterior to the analysis of the relational properties statically exemplified by words at different stages of the evolution of the language. Stipulates that any individual that is in the extension of 'bachelor' is not in the extension of 'married'.

Meaning postulates can be seen either as restrictions on possible worlds or as relativizing analyticity to possible worlds. On the former option we shall say that "If Paul is a bachelor then Paul is unmarried" holds in everyadmissible possible world, while on the latter we shall say that it holds in every possible world in which holds. Carnap regarded the two options as equivalent; nowadays, the former is usually preferred. Finally, classical lexicography and the practice of writing dictionaries played an important role in systematizing the descriptive data on which later inquiry would rely to illuminate the relationship between words and their meaning. Putnam's claim that it was the phenomenon of writing dictionaries that gave rise to the idea of a semantic theory is probably an overstatement.

But the inception of lexicography certainly had an impact on the development of modern theories of word meaning. The practice of separating dictionary entries via lemmatization and defining them through a combination of semantically simpler elements provided a stylistic and methodological paradigm for much subsequent research on lexical phenomena, such as decompositional theories of word meaning. More on classical lexicography in Béjoint , Jackson , and Hanks . Obviously, the endorsement of a given semantic theory is bound to place important constraints on the claims one might propose about the foundational attributes of word meaning, and vice versa.

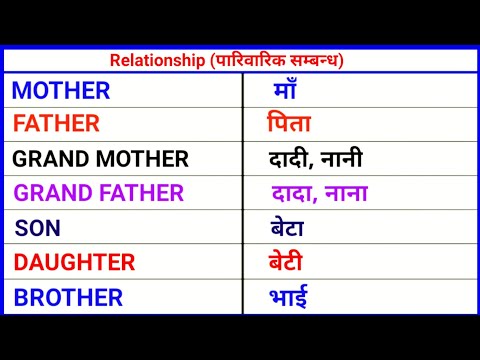

Semantic and foundational concerns are often interdependent, and it is difficult to find theories of word meaning which are either purely semantic or purely foundational. According to Ludlow , for example, the fact that word meaning is systematically underdetermined can be explained in part by looking at the processes of linguistic negotiation whereby discourse partners converge on the assignment of shared meanings to the words of their language . However, semantic and foundational theories remain in principle different and designed to answer partly non-overlapping sets of questions. It helps you understand the word Relation with comprehensive detail, no other web page in our knowledge can explain Relation better than this page.

The page not only provides Urdu meaning of Relation but also gives extensive definition in English language. The definition of Relation is followed by practically usable example sentences which allow you to construct your own sentences based on it. You can also find multiple synonyms or similar words of Relation. All of this may seem less if you are unable to learn exact pronunciation of Relation, so we have embedded mp3 recording of native Englishman, simply click on speaker icon and listen how English speaking people pronounce Relation. We hope this page has helped you understand Relation in detail, if you find any mistake on this page, please keep in mind that no human being can be perfect.

The Generative Lexicon theory (GL; Pustejovsky 1995) takes a different approach. Instead of explaining the contextual flexibility of word meaning by appealing to rich conceptual operations applied on semantically thin lexical entries, this approach postulates lexical entries rich in conceptual information and knowledge of worldly facts. According to classical GL, the informational resources encoded in the lexical entry for a typical word w consist of the following four levels.

What Is The Meaning Of In Regards To For NSM, word meanings can be exhaustively represented with a metalanguage appealing exclusively to the combination of primitive linguistic particles. Conceptual Semantics proposes a more open-ended approach. According to Conceptual Semantics, word meanings are essentially an interface phenomenon between a specialized body of linguistic knowledge (e.g., morphosyntactic knowledge) and core non-linguistic cognition.

Word meanings are thus modeled as hybrid semantic representations combining linguistic features (e.g., syntactic tags) and conceptual elements grounded in perceptual knowledge and motor schemas. For example, here is the semantic representation of 'drink' according to Jackendoff. Introduced by Trier , it argues that word meaning should be studied by looking at the relations holding between words in the same lexical field. A lexical field is a set of semantically related words whose meanings are mutually interdependent and which together spell out the conceptual structure of a given domain of reality. Lexical Field Theory assumes that lexical fields are closed sets with no overlapping meanings or semantic gaps.

Whenever a word undergoes a change in meaning (e.g., its range of application is extended or contracted), the whole arrangement of its lexical field is affected . States the truth conditions of the English sentence "If the weather is bad then Sharon is sad". Of course, is intelligible only if one understands the language in which it is phrased, including the predicate 'true in English'. Unfortunately, few of such extensions were ever spelled out by Davidson or his followers.

Moreover, it is difficult to see how, giving up possible worlds and intensions in favor of a purely extensional theory, the Davidsonian program could account for the semantics of propositional attitude ascriptions of the form "A believes (hopes, imagines, etc.) thatp". The notions of word and word meaning are problematic to pin down, and this is reflected in the difficulties one encounters in defining the basic terminology of lexical semantics. In part, this depends on the fact that the term 'word' itself is highly polysemous (see, e.g., Matthews 1991; Booij 2007; Lieber 2010). Before proceeding further, let us then elucidate the notion of word in more detail (Section 1.1), and lay out the key questions that will guide our discussion of word meaning in the rest of the entry (Section 1.2). In language, Every lexical item of the word, which we use in language, has meaning.

Sometimes it happens that one word s related to another in terms of meaning. This semantic relationship between two or more words is called meaning relations. Finally, a few words on the distinction between the inferential and the referential component of lexical competence. As we have seen in Section 3.2, Marconi suggested that processing of lexical meaning might be distributed between two subsystems, an inferential and a referential one. Beginning with Warrington , many patients had been described that were more or less severely impaired in referential tasks such as naming from vision , while their inferential competence was more or less intact.

The complementary pattern (i.e., the preservation of referential abilities with loss of inferential competence) is definitely less common. Still, a number of cases have been reported, beginning with a stroke patient of Heilman et al. , who, while unable to perform any task requiring inferential processing, performed well in referential naming tasks with visually presented objects . For example, in a study of 61 patients with lesions affecting linguistic abilities, Kemmerer et al. found 14 cases in which referential abilities were better preserved than inferential abilities.

More recently, Pandey & Heilman , while describing one more case of preserved naming from vision with severely impaired naming from definition, hypothesized that "these two naming tasks may, at least in part, be mediated by two independent neuronal networks". Thus, while double dissociation between inferential processes and naming from vision is well attested, it is not equally clear that it involves referential processes in general. On the other hand, evidence from neuroimaging is, so far, limited and overall inconclusive. Some neuroimaging studies (e.g., Tomaszewski-Farias et al. 2005, Marconi et al. 2013), as well as TMS mapping experiments (Hamberger et al. 2001, Hamberger & Seidel 2009) did find different patterns of activation for inferential vs. referential performances. However, the results are not entirely consistent and are liable to different interpretations.

For example, the selective activation of the anterior left temporal lobe in inferential performances may well reflect additional syntactic demands involved in definition naming, rather than be due to inferential processing as such . Developments of the approach to word meaning fostered by cognitive linguistics include Construction Grammar , Embodied Construction Grammar (Bergen & Chang 2005), Invited Inferencing Theory (Traugott & Dasher 2001), and LCCM Theory . The notion of a frame has become popular in cognitive psychology to model the dynamics of ad hoc categorization (e.g., Barsalou 1983, 1992, 1999; more in Section 5.2).

General information about the study of word meaning in cognitive linguistics can be found in Talmy , Croft & Cruse , and Evans & Green . Historical-philological semantics incorporated elements from all the above classical traditions and dominated the linguistic scene roughly from 1870 to 1930, with the work of scholars such as Michel Bréal, Hermann Paul, and Arsène Darmesteter . In semantics, reference is generally construed as the relationships between nouns or pronouns and objects that are named by them. The word "it" refers to some previously specified object.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.